Food Desert Mythology

Why Putting a Supermarket in a Neighborhood Won't Make People Eat Healthier

I’ve had the pleasure of reading the myth-busting “Retail Inequality: Reframing the Food Desert Debate” by Kenneth H. Kolb. I just started it and it is blowing my mind. I think it is utterly disruptive. I suspect this isn’t the last time you will hear me talk about it as I work and highlight my way through it.

The book was nominated for a James Beard Foundation award and even though it was beaten by what I’m sure is a fantastic book, that I also want to read, I feel like this book is shaking my earth a little bit and should shake yours. Mostly, it is telling us that this thing we have believed for the longest time - that poor people who live in food deserts eat less healthy foods because they have less access to good food and simply need more grocery stores to change their diets - is a complete myth, with all kinds of weird-ass assumptions that we created.

Essentially researchers and policy makers in the upper classes have made some conclusions about poor people without actually checking in with said poor people.

Like we made it up!

Back in the 90’s the “food desert” concerns became a thing.

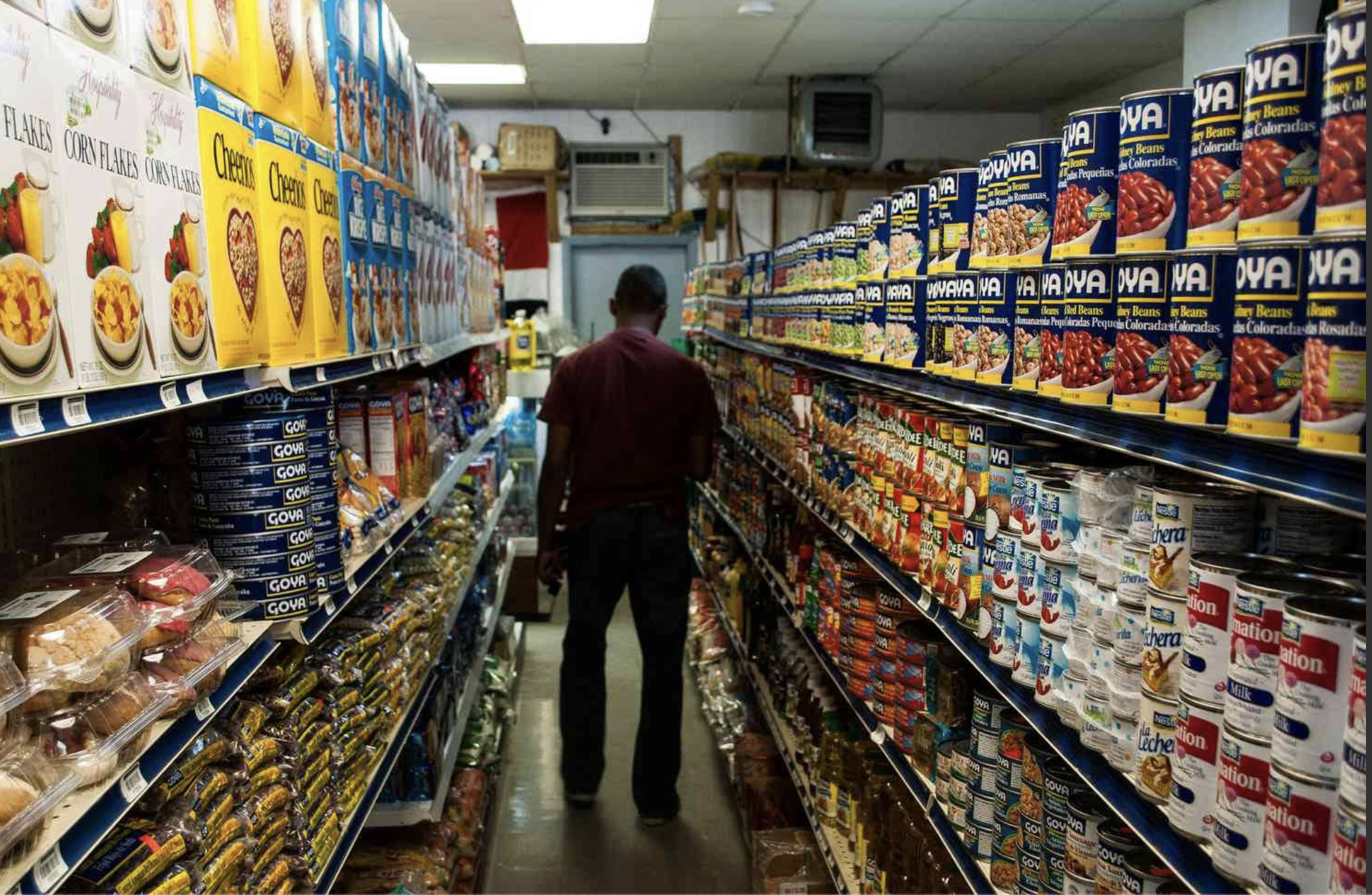

Food deserts were defined by the USDA as communities with a poverty rate of 20% and higher, median family incomes below 80% of surrounding areas, and at least 500 people living more than a mile from a grocery store. The idea was that residents of food deserts didn’t have local supermarkets and instead the food people could access tended to be from gas stations, dollar stores and convenience shops, places that notoriously offer lots of packaged and processed choices at higher prices, but not greens, vegetables and whole foods. The idea was that if these communities had proper supermarkets, these folks would choose to eat a salad over a Hot Pocket and this would impact health and happiness over a lifetime.

But this is a perfect example of how one community comes in (higher socio-economic class, largely white people) and assesses another community (lower socio-economic class, largely people of color) infusing their own class-centric ideas into what they see and experience.

Kolb’s book takes this apart and backs it up with a lot of research, his own and others.

One of the things I really love in scholarship is when people challenge everything about a concept. Here, Kolb does this by asking: Not just what is a food desert, but does it actually exist?

I try to do this when I can in my book because for years, I accepted that what the pros told me is how things work. But experience and maturity tell me that every human construct should be challenged, picked through and audited. We should not accept that things work a certain way for a reason. We must acknowledge that systems need to shift and change as people get better and more information and understanding is out there.

So, why don’t food deserts exist?

Turns out people inside these areas labeled as food deserts weren’t really upset about their diets. According to Kolb, these people wanted assistance improving their communities, making their neighborhoods safer, better and stronger. When Black community activists asked for access to healthier foods, researchers believed that meant better access to a proper grocery store, and based on this created all kinds of interventions to help bring supermarkets to depleted areas. But this missed the point.

Food does not exist in a kind of lone sphere, where it’s just food and what you want to make for dinner and what techniques and tools you’ll use to make that dinner happen.

As I have written about here and again, in my book, food is deeply connected and intersectional to how people live, what kind of housing they have, what kind of kitchen, what kind of pantry, what kind of income, affordability of rents and how much housing is available, cultural underpinnings about caregiving and food in general, generational pulls, the quality of people’s mental health, the extent of their sicknesses and disabilities, addictions, family separation through CPS overreach, the overarching influence of white supremacy and white flight, thoughtless gentrification and harmful urban planning, clumsy or non-existent public transportation and the resulting realities of school to prison pipelines in these communities.

Of course, when people wanted better access to food, we (media, activists, academics and journalists from the upper classes) found an easy-enough solution - bring in more grocery stores. It’s that simple.

Except it’s not.

Because we brought in grocery stores but never worked on the more complex and deeply-rooted areas that actually needed change. Don’t get me wrong: WE ALL wanted this to work. We all hoped this kind of response would change communities in big ways. Instead, in poor community after poor community, that grocery store that was invited in to solve all the food problems of the community, often enough went belly up and pulled out.

This is why Retail Inequality is such a disruptive book. Because it’s telling us, food writers, how we fucked this up by trying to apply easy solutions (build a store!) to intractable problems deeply rooted in 100 different ways that people are forced to live.

Supermarkets in small cities all over the country, in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and the Bronx all went belly up. The people in these communities continued to travel the same distances to shop at their old grocery stores and kept eating the exact same kinds of foods. Nothing changed because we brought in new grocery stores.

In fact, researchers found that “more than half of food desert residents bypassed their closest grocery stores” and chose their preferred grocery store miles away.

Basically Kolb points out that these neighborhoods have “bad retail.” These are businesses that trap and exploit people in the lower classes, taking their money for little gain. Think: pawn shops, liquor stores, lottery places, convenience stores and blood plasma centers that people use to make quick cash. They are allowed to proliferate because of, well, unobstructed capitalism. A lack of a community plan. I lack of care around people of color. All of it.

But still, even people surrounded by these bad retail, 85% of those people buy their food from supermarkets. Many residents traveled an average of 3.6 miles to get to a preferred market. They also found that proximity to nutritious food had little impact on changing diets. Geography, it turns out, has nothing to do with how people select food.

And now the kicker.

Access to a supermarket “has little effect on healthy eating.”

Astounding. Our simple solution to a complex problem didn't work. Who knew!

Kolb’s book goes into mad detail about how we all jumped on board the food desert assumptions and how we all wanted to magically believe that a grocery store, a wall of beautiful fresh vegetables, could change taste preferences, just by being there. When in fact, most people's food choices - like everyone across race, gender and class - are made based on the “resources and constraints of our everyday lives.”

Basically how we eat reflects how we live.

“We feed our kids mac and cheese because it's the end of the month and I want to make sure my kids belly is full.”

“I am working two jobs and don't have time to cook, so we ate frozen dinners.”

“My kitchen stove isn’t working so we will order from Wing Stop.”

“We were between school and after care so we grabbed McDonalds.”

“After this hellish day, I can’t bear to stand at the stove, I’m making the kids sandwiches and chips. This will have to do.”

“I picked up a box at Salvation Army today, so we are having hamburger, boiled potatoes and carrots again”

“My air conditioner isn’t working and I’m not starting the oven.”

“I’m trying to get fit, so I bought a lot of stuff to make salads for lunch at work.”

These are quotes from people I have talked to about how they are choosing their food. So if we want people to have healthier diets, we need to tackle their issues of lifestyle. The food gets better, healthier, and people get pickier about their diets when their lives get better, when they have the brain space to consider it.

And this goes back to solving the problems of poverty, laid out in Poverty, By America, by Matthew Desmond, which I’ve broken down for you here. Once we raise people up, supplement their incomes, raise wages, make the rich pay their share, destroy white supremacy, mend generational trauma, then food choices will change.

That sounds like a lot.

Oof. It is. But the baby steps count.

We have to keep pushing.

+++++

An example of what Kolb discusses in his book came on the radio while I was driving kids to camp this morning.

Turns out, a recent study in Nevada - my state - showed that “75% of Nevada children (0-5) do not have access to licensed childcare, which impedes their parents’ ability to work.” This keeps people, often women, out of the workforce and supporting their families. Families experience more poverty and instability because of it.

Ironically, Nevada is a desert that might also be an actual “childcare desert,” if such a thing exists.

This is an important consideration as Nevada today officially welcomed the Oakland A’s into its portfolio of stadium teams, and continues to build and entice new industry, like tax breaks for film productions companies. (Apparently, Las Vegas is one big giant suburb of California now. LOL.) As we plan these new initiatives we have to also focus on the infrastructure, the foundation, water and land conservation, and how to support our communities so they can work, benefit and participant amply in Nevada life.

Which brings me to why this newsletter is so often so much not about food specifically, like no recipes. No discussions of how to properly caramelize onions or the mechanics behind achieving wok hei. I’ve realized, as I keep writing here, that my food writing has to be about more than that, too, otherwise whatever food we talk about exists and lives only for certain people, those who have privilege and access at any given time.

Our food and food choices are the result of how we live, how we treat each other, how we interconnect, how we struggle. We cannot give people more choice or encourage them to eat better when we are simultaneously slamming them by ignoring poverty and circumstance.

Kolb believes that the research on supermarkets and food deserts didn’t consider three important issues; 1) how much social capital people had (the amount of support from friends, family and community) who can take them to a store, who can pick up groceries for them, etc. 2) Household dynamics, do they have kids, elderly people, how many people work, is there affordable daycare and good schools, etc) and this is a big one…

3) taste for convenience.

Soon, following a discussion I had on the City Cast Las Vegas podcast called “How to Fix School Lunch” I’m going to write about how processed food manufacturers set the taste preferences for entire communities through school lunch and pantry programs, and some ways communities can fight back, one school at a time.